Articles

Methodology

Clicker Training Fundamentals

What is coercion?

What counts as punishment? What is an “aversive”?

What is wrong with punishment?

Preventing the occasion for punishment and coercion

Training Success: It is Up to You

Why do you like mules? What can you do with mules?

Methodology

My training method is based on the principles of operant conditioning. It is a combination of: positive reinforcement (clicker training), breaking behaviors down into achievable pieces, advance and retreat, and pressure and release of pressure.

Clicker training is a systematic method of using positive reinforcement that creates a very clear line of communication with the horse.

Breaking behavior down into easily achievable pieces makes the horse feel successful the entire time. If the horse does not want to do something, or shows signs of annoyance, fear, or discomfort, I listen and address the problem without forcing the animal to do it anyway.

Breaking behavior down into easily achievable pieces makes the horse feel successful the entire time. If the horse does not want to do something, or shows signs of annoyance, fear, or discomfort, I listen and address the problem without forcing the animal to do it anyway.

Using advance and retreat helps the horse overcome fears in a non-confrontational way.

Pressure and release of pressure are our main methods of communicating while riding. Pressure is anytime we use our hands, posture, reins or lead ropes, legs and seat to ask for something. Release tells the horse they complied with our request. Every horse can be light and sensitive so when I am training with pressure and release, I only use the amount of pressure that I would use on a light, trained horse, and reinforce when the horse starts to go in the direction I want.

Clicker Training Fundamentals

Clicker training is a communication system using a marker signal and positive reinforcement.

The marker signal means yes, that was right, your reward is on the way! The marker signal can be anything the horse can perceive, but it should not have any other meaning to the horse. Usually we use a click—usually starting with a mechanical clicker, and quickly transitioning to a click we make with our mouths. The mouth-click is different from any other verbal signal we give to our animals such as the go-forward-cluck.

Finding an effective positive reinforcer is vital to the process. For equines, this is mainly a food reward such as a teaspoon of grain, a small slice of carrot or apple, a bite of green grass, or a few hay stretcher pellets. Some equines will work for scratches on itchy parts of their bodies, but I have found using scratches to have limitations. Almost all horses prefer food to scratching, and if a horse is stressed scratches are usually no longer reinforcing. It is possible to create other reinforcers and to teach animals to accept them in the place of food reinforcers, however, most of the time when we are teaching our horses, we use food rewards. The important question to ask yourself is: Is what I am offering actually reinforcing to the horse, or do I just think it should be reinforcing? Is the horse working hard to earn his treat?

You may ask: But won’t hand feeding cause my horse to have bad manners? When used properly, the answer is no. When I introduce clicker training to a new horse, I set up the situation so that the horse learns that mugging produces nothing, but paying attention to me and engaging in what I want them to do is a fast, fun, and easy way to get food rewards. It is important that we are safe around our 1000 pound animals with our pockets full of goodies!

The basic method is to watch for the behavior you want to see more of, click, then reinforce. The horse learns to repeat what he was doing when he heard the click. Clicker training is a tool that allows you to say yes! I like that, do it again!

When we teach something with clicker training we teach individual components of a behavior separately, then put those parts together. We also start a tiny piece and gradually build on that until we have reached our goal.

If the horse does something we don’t like: we keep ourselves safe, we ignore the behavior (if possible), and we focus on teaching the horse what he should do in that situation.

There are some foundation behaviors I like to teach in the beginning stages of training. The process of learning these behaviors creates a solid understanding of clicker training in both the equine and the owner. These behaviors are also key components making your horse manageable and to creating maximum performance.

What can you teach with clicker training?

Anything you can teach with other training methods, and definitely more! The difference is that if you trained it completely with clicker training (and didn’t sneak any aversives into the process) your horse would love their job. And clicker training can get you things that traditional methods never can. You can train a horses to fetch, even if they didn’t already have the inclination to carry things in their mouths. You can train a horses to put their noses in their halters, play basketball, collect the mail from the mailbox, lie down without ropes or force, move in collection, or align themselves to the mounting block with no cues whatsoever. You can train a new behavior without moving anything except to click and deliver the food; this training without any prompting is called free shaping. You probably cannot teach a horse to fear you with clicker training, however, but if you are reading this you are probably not interested in that kind of relationship!

Anything you can teach with other training methods, and definitely more! The difference is that if you trained it completely with clicker training (and didn’t sneak any aversives into the process) your horse would love their job. And clicker training can get you things that traditional methods never can. You can train a horses to fetch, even if they didn’t already have the inclination to carry things in their mouths. You can train a horses to put their noses in their halters, play basketball, collect the mail from the mailbox, lie down without ropes or force, move in collection, or align themselves to the mounting block with no cues whatsoever. You can train a new behavior without moving anything except to click and deliver the food; this training without any prompting is called free shaping. You probably cannot teach a horse to fear you with clicker training, however, but if you are reading this you are probably not interested in that kind of relationship!

What is coercion?

Coercion is the use of punishment and the threat of punishment to get the horse to do what we want. It is also when we use punishment and threats in order to reward the horse by letting him escape. I think of coercion as when the horse does not have the option of making a choice. It is coercion the horse is faced with “do it... or else.” It is coercion when the horse is nagged until he performs. It is coercion when the horse is punished when he does not respond to a cue. It is when the horse is put into an uncomfortable or scary situation he needs to find his way out of. It is coercion when a horse is forced to exercise until he submits. It is coercion when the horse is operating under a threat, or when you use a poisoned cue. (A poisoned cue is when you present a cue, and if the horse performs correctly he gets a reward, but if he doesn’t perform it correctly, he gets a correction. The ambiguity of the consequences causes apprehension in the horse, and he dreads the presentation of the cue.

Equines experience enough coercion in their surroundings as it is, and we don’t need to add more stress to their lives. Some examples of coercion they might need to deal with on a regular basis: herd hierarchy, standing for the vet or farrier, traveling in trailers, going to shows, being isolated in stalls, and generally being made to do things they are unenthusiastic about. I continually work on eliminating sources of coercion in my training. The more I learn about training with positive reinforcement the better I become at finding alternatives to coercion. Just knowing there are viable alternatives to using coercion creates the space for gentler solutions.

Equines experience enough coercion in their surroundings as it is, and we don’t need to add more stress to their lives. Some examples of coercion they might need to deal with on a regular basis: herd hierarchy, standing for the vet or farrier, traveling in trailers, going to shows, being isolated in stalls, and generally being made to do things they are unenthusiastic about. I continually work on eliminating sources of coercion in my training. The more I learn about training with positive reinforcement the better I become at finding alternatives to coercion. Just knowing there are viable alternatives to using coercion creates the space for gentler solutions.

What counts as a punishment? What is an "aversive"?

A punishment is anything that decreases the future occurrence of a behavior. An aversive can be anything that a horse finds painful, uncomfortable, frustrating, or irritating. Usually when we offer an aversive it is a punisher, but sometimes it isn’t actually effective. Also, if your cue to start a behavior, such as a canter depart, is an aversive, when you ask for the canter, you are punishing the behavior that was occurring when started to ask for the canter depart. So, if your horse was trotting quietly and you ask for a canter depart (and the horse doesn’t like how the cue for canter depart feels, or it reminds him of something painful or scary that happened in the past) you may just have punished the nice quiet trot. Over time, you horse will be less likely to trot quietly, and may become more nervous at the trot or less cooperative about moving forward at the trot at all.

Sometimes we do something by accident that punishes a behavior that we wanted to reinforce. We have to watch the horse’s body language for signs that we are inadvertently using aversives, or that our training has become frustrating or worrying to the horse. Here are some hints that your horse has found something aversive:

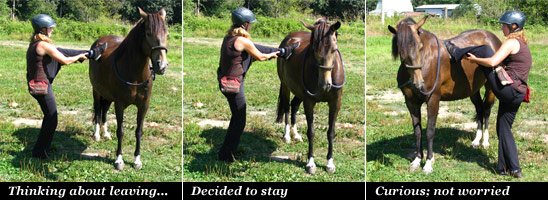

The horse has her ears partway back, eyes half-slits, nostrils pinched, head up, neck and back hollowed and tense—as shown in the first image, the horse is thinking about leaving. Here I have put my foot up onto Poetica’s back, and she is definitely worried about it, and she’s thinking about whether she wants to stay.

If I were to push her, she would leave, but I wait... and as shown in the second image, she decides to stay.

In the third image, she is watching me and she is curious about what I am doing, but not really worried.

Tail clamped, haunches bunched up, belly muscles tense

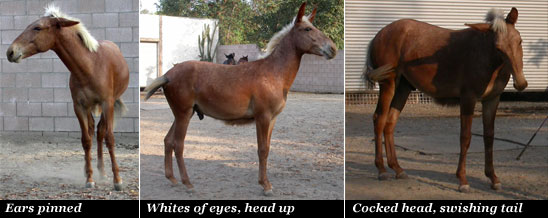

Tail swishing, ears pinned for a moment or more (shown in first picture below)

Eyes white, head thrown up, leaning away from you or the scary thing, head and ear cocked to whatever is scary (shown in second and third pictures below)

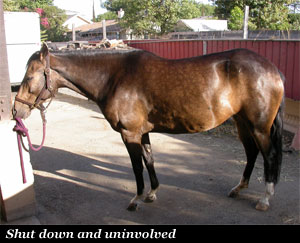

Another way a horse or mule might show us that we have used aversives is to just shut down. The horse might try to leave, get distracted, become unfocused, or (as shown in the picture to the right), just become uninvolved.

Another way a horse or mule might show us that we have used aversives is to just shut down. The horse might try to leave, get distracted, become unfocused, or (as shown in the picture to the right), just become uninvolved.

What is wrong with punishment?

Punishment is a training tool that every horse person is familiar with, and it is very casually used in the horse world. Nearly everyone has done this: Your horse gets into your space, and you smack him with the lead rope or jerk on his halter... In fact, clinicians and trainers tell us that we need to punish our horses in order to earn “respect.” The problem with punishment is it has so much potential for wrecking a trusting relationship between horse and human. A horse who is anticipating punishment is not thinking sweet thoughts about her handler. The fallout from using punishment can range from standoffishness, fearfulness, and panic, to irritability, defensiveness, anger, aggression, and desire for revenge. Another disadvantage to using punishment is that it can often cause irritating or dangerous behavior to escalate into even more dangerous behavior. Horses rarely respond to punishment by calming down. Horses and their handlers have been hurt countless times as a result of punishment.

Punishment is a training tool that every horse person is familiar with, and it is very casually used in the horse world. Nearly everyone has done this: Your horse gets into your space, and you smack him with the lead rope or jerk on his halter... In fact, clinicians and trainers tell us that we need to punish our horses in order to earn “respect.” The problem with punishment is it has so much potential for wrecking a trusting relationship between horse and human. A horse who is anticipating punishment is not thinking sweet thoughts about her handler. The fallout from using punishment can range from standoffishness, fearfulness, and panic, to irritability, defensiveness, anger, aggression, and desire for revenge. Another disadvantage to using punishment is that it can often cause irritating or dangerous behavior to escalate into even more dangerous behavior. Horses rarely respond to punishment by calming down. Horses and their handlers have been hurt countless times as a result of punishment.

Yet another drawback to punishment is the effect on the handler. When the horse is behaving “badly” and the handler interrupts the behavior by using punishment, it is a big relief to the trainer. The trainer feels successful and powerful and feels like her punishment was effective—regardless of whether the future likelihood of the behavior is decreased or not! This makes the trainer more likely to use punishment whether or not it is working. The trainer becomes sucked into a downward spiral of using punishment that is difficult to escape. It affects the way the trainer thinks about the horse, since a horse that is “good” does not need punishment and a horse that is “bad” does. In addition, the trainer is going to be on the lookout for wrong answers that need to be punished, instead of thinking about all of the things that the horse is dong right.

Furthermore, it is difficult to use punishment for its intended purpose—to prevent an annoying or dangerous behavior from happening again. In order for a punishment to work a number of things must be true:

- Accurate timing: the punishment must occur during the undesired behavior, ideally right as it starts. If the punishment happens right after the behavior, there is a good chance that the horse will not connect the punishment to the behavior, in which case, you are punishing something else, usually perfectly acceptable behavior.

- Severity: The punishment must be sufficiently severe in order to deter the horse from trying it again. If the punishment is not severe enough to prevent future occurrences then the trainer must try something more severe. In the mean time, the horse gets hardened to the current level of punishment. If you continue to raise the level of punishment in small increments you will soon be using a brutal level of punishment, but it still will not be effective. However, if you jump to too severe a punishment it could endanger the horse’s physical or emotional welfare.

- Consistency: The punishment must happen every time the behavior occurs. If one behavior goes unpunished, the horse may be confused as to what is being punished. The horse may think that he is allowed to perform the behavior in certain circumstances, but not others. This requires that the handler always be on the lookout for punishable behaviors, which is not a good state of mind to practice.

- Must be present: The punishing agent must be present in order to mete out the punishment. You must be able to perceive the behavior occurring as well. Let’s pretend that we are trying to use punishment to get rid of pawing at the stall door at feeding time. If you manage to punish the horse for lifting his leg when he first begins to paw (timing) with a nasty enough aversive that he doesn’t want to be repeated (severity), and you catch him every single time he starts to paw, then the horse should paw less and less when you are there. But as soon as you walk around the corner, the “punishing agent” (you) are not there, and the horse is free to paw.

- Number of punishments: If it takes more than a few punishments to decrease the occurrence of the behavior, then the punishment is not working, and the trainer must try something else. If you continue to try to use the punishment and it is not working, then you are being annoying at best, or perhaps you are being abusive.

- Random punishments: After a behavior is successfully punished (no longer occurs) you still need to ensure that the behavior stays gone by showing that you have the power to punish. This is done by offering a random, preemptive punishment, even when the horse has done nothing wrong, whatsoever.

Experts in horse behavior specialists and behavior analysis are strongly opposed to the use of punishment. Sue McDonnell, PhD, Certified AAB talks about using positive reinforcement training instead of punishment in these articles (will open in a new window):

- Positive Reinforcement

- Horse Behavior: War on Punishment

- Study Correlates Food Reinforcement with Positive Responses during Training

- Teaching Old Ponies New Tricks: Positive Reinforcement Effective

- Behavior: Discipline for Kicking and Striking

- Licking/Chewing=Learning?

In conclusion, it is nearly impossible to correct unwanted behavior with punishment since if any one of the requirements is not met, it will probably not be effective. You also need to ask yourself if it is worth it to you to use punishment since it is likely to damage you relationship with your horse or cause other problems which may be more annoying or dangerous. Just thinking about fulfilling the last requirement (random punishments) leaves me feeling sick. The good news is you do not need to use punishment at all. You can program yourself to ignore unwanted behavior, and learn the skills you need in order to change your horse’s behavior non-violently.

Preventing the Occasion for Punishment and Coercion

What can we do instead? That is one of the sets of skills I endeavor to teach. I want owners and riders to be proficient at using positive reinforcement, knowing what to train, training using small incremental steps, identifying and filling in training holes, having nonaggressive, confident and clear body language, being gentle and unambiguous when rope handling and riding, thinking in terms of what we want instead of what we don’t want, and finding and removing any triggers for undesirable behavior.

I also train in a way that prevents unwanted behavior from occurring in the first place. When a horse knows what we want him to do, he is less likely to do something else that we don’t want him to do. When a horse is busy doing something we want, he can’t also be doing something we don’t like.

Horses exposed to traditional training often think in terms of what bad things might happen to them, how little they need to do in order to avoid correction, or how they can avoid the people around them or the nasty things that might happen to them. When I work with a horse, he increasingly concentrates on what he can do to please me. My training method releases a horse from worry about coercion and gets him in the habit of answering “yes” to any requests.

Training Success: It Is Up To You

Training success is not the horse’s responsibility; it is the trainer’s responsibility. You cannot blame a training failure on your horse. When you look at training with this frame of mind you suddenly have a lot more control and a lot more responsibility. If you are not successful it might be because: the horse cannot do what you are asking (is physically incapable of performing that behavior), the horse is in pain, the horse is fearful, the horse has been trained to do something else and you have to change his response, or the horse doesn’t understand what you want and why he should do it. Occasionally, the horse decides that your reinforcers are not worth the effort, and he is telling you he has a preference to do or not do something you are asking. It is your job to make the task easier or the payoff more valuable. It takes some practice to figure out what to do when you are not successful. It takes even more time to see the precursors to failure, and make changes before you make mistakes in your training.

Why do you like mules? What can you do with mules?

I like mules because I have found them to be more affectionate than horses. I like the training challenges they present. I love their long ears! Mules are able to do just about anything you can do with a horse, and maybe more! A mule is a hybrid cross between a jack (donkey stallion) and a horse mare. Due to hybrid vigor, mules get a little bit of the best from mother and father. Mules tend to live longer than horses, and they are also less likely to get sick or injure themselves. Donkeys are a mountain species, and instead of running when they are frightened they may chose to stand and fight instead; some mules seem to inherit this bravery. Donkeys and mules are often used to protect livestock from coyotes, birds of prey, and even cougars and bears! Mules are very smart and learn new behaviors quickly and easily. Mules tend to be more sure of themselves and if they think they are doing what is best it can be hard to persuade them to do something different. They have a strong sense of self-preservation, which can make them seem stubborn if you are trying to force them to do something they aren’t sure is a good idea. Because of this, mules are less tolerant of coercion and punishment than horses, so those tools are much more off limits to mule trainers. There is a saying about trainers: “A good horse trainer is not necessarily a good mule trainer, but a good mule trainer is always a good horse trainer.” Since I do not rely on punishment or coercion for my success I get along really well with both horses and mules.

I like mules because I have found them to be more affectionate than horses. I like the training challenges they present. I love their long ears! Mules are able to do just about anything you can do with a horse, and maybe more! A mule is a hybrid cross between a jack (donkey stallion) and a horse mare. Due to hybrid vigor, mules get a little bit of the best from mother and father. Mules tend to live longer than horses, and they are also less likely to get sick or injure themselves. Donkeys are a mountain species, and instead of running when they are frightened they may chose to stand and fight instead; some mules seem to inherit this bravery. Donkeys and mules are often used to protect livestock from coyotes, birds of prey, and even cougars and bears! Mules are very smart and learn new behaviors quickly and easily. Mules tend to be more sure of themselves and if they think they are doing what is best it can be hard to persuade them to do something different. They have a strong sense of self-preservation, which can make them seem stubborn if you are trying to force them to do something they aren’t sure is a good idea. Because of this, mules are less tolerant of coercion and punishment than horses, so those tools are much more off limits to mule trainers. There is a saying about trainers: “A good horse trainer is not necessarily a good mule trainer, but a good mule trainer is always a good horse trainer.” Since I do not rely on punishment or coercion for my success I get along really well with both horses and mules.